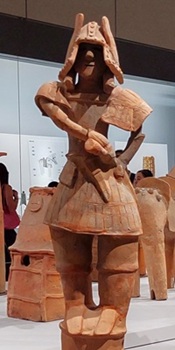

Today on Museum Bites we’re taking a stroll through Japanese tomb art called haniwa. Popular during the Kofun Period (c250 to c600 CE), these delightful figures give us a glimpse of Japanese culture at a time when a written language was not prevalent. Join me for a closer look at a haniwa shrine maiden on display at the Tokyo National Museum.

Haniwa, meaning clay cylinder or ring, are handcrafted, hollow, and unglazed terracotta sculptures that range in size from 1 to 5 feet tall. They are often incised and decorated with white, red, or blue paint. Let’s zoom in on our lovely shrine maiden’s details.

Haniwa Priestess (6th century)

Tokyo National Museum

Photo by cjverb (2025)

Note how her face is smooth, but lacks any detail or individuality, aside from her eyebrows and the red stripes of paint that flow from her eyes down to her chin. One outstretched hand offers a bird-headed cup and the other presses against her breast. The cup contains alcohol, a gift she extends to the gods. This offering and her face paint indicate she is a priestess.

Haniwa Priestess (6th century)

Tokyo National Museum

Photo by cjverb (2025)

The richness of her clothing and jewelry also signify her high rank. Her dress is painted and incised with geometric designs described by the Tokyo National Museum as “magical patterns”. A cylindrical base provides support where legs and feet are lacking.

Haniwa Priestess (6th century)

Tokyo National Museum

Photo by cjverb (2025)

Tomb Art: Haniwa were placed on top of kofun, massive burial mounds typically shaped like a key-hole and surrounded by a moat. Popular during the aptly named Kofun Period (c250-c600 CE), these elaborate tombs were built for emperors and the ruling elite.

Left: Nintoku-tenno-ryo Kofun, Sakai, Osaka, Photo by UNESCO

Right: Haniwa (reconstruction), Sakuyama Kofun, Photo by Saigen Jiro

The earliest haniwa were simple and cylindrical, but by the 400s CE, the demand grew for more elaborate and figural (i.e., animal and human) forms, in addition to the simple cylinders.

Left: Haniwa House (Kofun Period), Kashihara Archaeological Inst, Photo Saigen Jiro, Wikimedia

Right: Haniwa Horse, (400s–500s CE), Cleveland Museum of Art

The cylindrical haniwa typically marked the perimeter of a tomb, while the more ornate haniwa were arranged in specific groupings, possibly to mimic a village. A haniwa house was usually placed at the center. The type of haniwa created for the tomb may indicate what role they were meant to play in the deceased’s afterlife. For example, a warrior would provide protection, and a priestess would communicate and make offerings to the gods. This could also explain why haniwa clothing and accessories are more detailed than their faces and bodies, because they provide visual clues to each haniwa’s specific role.

Haniwa Warrior (6th century)

Tokyo National Museum, Photo by cjverb (2025)

Clues to the Past: Since a written language was not prevalent at this time in Japan, the exact meaning and significance of the haniwa is unclear, but they are still rich with information. For example, we have a better understanding of Japanese burial practices such as the dead were buried instead of cremated. The haniwa also give us a glimpse of the architecture, fashion (clothing, hairstyles, jewelry), weapons, and other accessories like helmets, saddles and bridles from this era.

Haniwa Musician Playing a Zither (Kofun Period)

Miho Museum

Clues to Japanese social structure are also evident. In addition to an elite class, artisan (potters, musicians, dancers), military (warriors, war horses), religious (priestesses), and farming (farmers, farm animals) classes were also present during the Kofun Period. Haniwa production and mass graves began to wane in the latter half of the 6th century when Buddhism and its practice of cremation was on the rise in Japan.

Mayumi Joutouguu, Touhou Project Character

Photo from Touhou Wiki

Today, you can find haniwa replicas decorating ancient tomb sites and parks, on sale in gift shops, and featured in manga (notice in the above image Mayumi Joutouguu’s haniwa necklace). Authentic haniwa, like our shrine maiden, are on display in museums across the globe. Go check it out!

Miko-san, Shimogamo Shrine, Kyoto

Photo by Mikel Lizarralde, Wikimedia Commons

But wait, that’s not all. Real life shrine maidens exist today. Miko-san are responsible for tending Shinto shrines throughout Japan. Click on this Life as a Shrine Maiden link to read about one woman’s experience.If you’d like to take a deeper dive into haniwa, click on this Google Arts & Culture: Haniwa link. Click on this Kofun link courtesy of the New York Times to learn more about these amazing tombs.

Arty Facts:

* Up to 20,000 haniwa could decorate a kofun.

* To date, 71 kofun have been discovered.

* The Nintoku-tenno-ryo Kofun in Sakai, Osaka is the largest (1,594 ft long by 115 ft high) and equal to 4 ½ football fields in length.

Dancing Haniwa, Tokyo National Museum

Photo Wikimedia Commons

That wraps up our look at Japanese tomb art. I’ll be back next week with more Museum Bites. Until then, be safe, be kind, and take care.

Cover photo by cjverb (2025)

Sources:

Asian Art Museum, San Francisco: Haniwa in the Form of a Warrior

Cleveland Museum of Art: Haniwa Figure of a Female

Cleveland Museum of Art: Haniwa Horse

Encyclopedia Britannica: Japan – Yamato, Buddhism, Decline

Encyclopedia Britannica: Haniwa

Encyclopedia Britannica: Kofun or Tumulus Period

Fitzwilliam Museum: Haniwa, a Female Figurine

Metropolis: Life as a Shrine Maiden: Part-Time Priestess

Miho Museum: Man Playing a Zither

New York Times: The Guardians of Japan’s Keyhole Tombs

Sakai City: Nintoku-tenno-ryo Kofun

Seelye, C., A History of Writing in Japan (1991)

Smart History: Haniwa Warrior (2015) by Yoko Hsueh Shirai

Tokyo National Museum: Development of Figural Haniwa Tomb Figurines

Tokyo National Museum: Haniwa Online Collection

Tokyo National Museum: Tomb Sculptures (“Haniwa”): Dancing People

Hey!

I was happy to see this new post. I’m glad to see you writing. Hope you are well. 🙂

-Georgia

LikeLike

Thank you!😊

LikeLike